WHAT IS IT?

Ostertagia ostertagi is one of the most common species of gutworm found in the UK. This small brown worm has a direct life cycle with no intermediate hosts, and can affect production parameters in both dairy and beef cattle.

WHAT IMPACT DOES IT HAVE?

Youngstock which have yet to develop immunity can be at serious risk from clinical disease (parasitic gastroenteritis/PGE). This is associated with large numbers of gutworms in the abomasum and intestines.

Ostertagiosis is associated with poor weight gain, poor body condition, scour and potentially death if very heavy worm burdens are present. There are two forms of ostertagiosis depending on the time of year; type 1, which is by far the more common, and type 2.

Type 1 ostertagiosis infection occurs when first grazing season calves become infected with overwintered larvae on pastures. Once these cattle develop adult worm burdens they begin to shed eggs onto pasture, contributing to pasture contamination. As these eggs develop to infective larvae, animals go through cycles of re-infection, rapidly amplifying pasture contamination. A similar pattern can occur in autumn-born beef calves turned out the following spring. It is possible to see disease as early as 4 to 6 weeks after turnout if pastures are heavily ontaminated from cattle grazing in previous years. The number of calves affected within the group is generally high but deaths are less common, especially if treatment is given early.

Type 2 ostertagiosis occurs in late winter or spring in cattle that were housed carrying high numbers of encysted Ostertagia larvae, ingested from the pasture in the autumn. Larval development becomes arrested within the host but when it resumes, large numbers of the parasite can mature at the same time, causing significant damage to the abomasal wall as they emerge. Usually only a small number of animals within a group are affected but death is not uncommon in those cases. Treating cattle at housing with a wormer that has efficacy against larval stages will prevent type 2 ostertagiosis.

Adult cattle, although resilient to the clinical disease associated with gutworm infection such as scour, have been found to carry worms numbering into the hundreds of thousands. These animals do suffer from sub-clinical disease, which leads to poor performance through decreased milk yield, poor appetite and reduced fertility.

Growing cattle take longer to reach target weight, which can increase age at first service and lead to overall reduced fertility throughout the animal's life. A delay in reaching target weights for fattening animals will also eat into profits. Research has shown that even immune cows, when exposed to a significant gutworm challenge, have a reduced appetite. Many studies have proven that even immune cattle carry a worm burden; being immune means the risk of developing clinical disease is extremely small. In adult dairy cows, eating less as a result of infection can have a direct effect on milk yield and reduce lactation by as much as 2.6 litres per cow per day.1

This effect on appetite can be particularly significant for newly calved cows, where maximising feed intake is important to reduce the ‘energy gap'. If appetite is reduced at this critical time and food intake is compromised, the negative energy gap will increase, causing the cow to milk off her back and lose significant body condition.

A recent study demonstrated that cows treated around the time of calving produced an average of 1 litre more milk each day for the entire lactation than those that were untreated.2

Studies have also shown that worming dairy cows can improve fertility, with treated animals demonstrating a 13-day shorter calving to conception interval and a 20% higher conception rate at first service.3

Gutworm Fact Sheet

For more Gutworm Resources

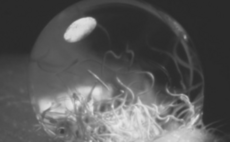

LIFE CYCLE

The life-cycle of Ostertagia is direct, which means that infection is picked up from the pasture, adult worms develop in the host, these worms produce eggs that seed the pasture with new infection ready to infect the nextgrazing host animal. No intermediate host is involved.

- Cattle can start to pick up the infective L3 stage larvae as soon as they are turned out to pasture in the spring. The L3 larvae are ingested and pass into the abomasum/intestine.

- The pre-patent period is the time it takes for these larvae (L3) to develop within the host animal into adult worms which start producing eggs. In the case of Ostertagia the pre-patent period is as short as three weeks.

- L4 larvae can remain dormant for up to five months within the abomasal wall of the host animal before completing development.

- This makes it possible for larvae that infect cattle at the end of the summer to overwinter in the host. They can then resume development the following spring when environmental conditions are more favourable.

- Eggs are then passed out in the dung onto the pasture, where they hatch to release first stage larvae (L1).

- Within the faecal pat the first stage larvae (L1) moult to become L2 and finally to the infective L3 stage, which migrate out of the faecal pats onto surrounding herbage where they can be eaten. This development phase can take as little as two-three weeks.

DIAGNOSTICS

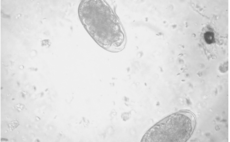

Faecal Egg Counts (FECs)

FECs can give an indication of the number of worms in the gut of young cattle, and provide a useful indicator of the need for treatment and the levels of pasture contamination. Once immunity starts to develop, FECs become less reliable, as the worms inside an animal shed fewer eggs. The MOO Test (Milk Ostertagia ostertagi ELISA) is a useful diagnostic tool in dairy herds. This herd test assesses the level of gutworm exposure cows have received by quantifying the amount of antibody to Ostertagia in a bulk milk sample. Where the level of exposure is determined to be high, Ostertagia is likely to be having a significant impact on productivity, and treatment of the herd is likely to yield an improvement in milk production.

TREATMENT AND MANAGEMENT

Beef and dairy youngstock

and can be used to treat and Control gutworms in youngstock. Treatment should be targeted at young cattle during their first and second grazing seasons. The timing of treatment should be based on an assessment of epidemiological factors and be customised for each individual farm. For youngstock on pasture that has not been previously heavily stocked or has been rested for several years without grazing cattle, monitoring of growth rates, and use of FECs can provide an effective means of assessing the gutworm challenge.

Dairy cows and heifers

Treatment to remove the gutworm burden at or shortly after calving helps to reduce the nutritional constraints on the animal, reducing the energy gap, and easing her transition into lactation. For cows calving in the spring, treating at or shortly after calving also allows farmers to make the most of their best and cheapest source of nutrition; grass.

is the tried and trusted treatment for gutworm in dairy cows. It has a zero milk withhold, allowing dairy cattle to be treated at the optimal time with no loss of production.

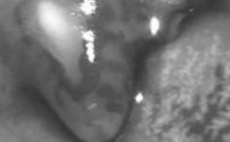

Animals affected by gutworms often display a loss of appetite with sudden and profuse green diarrhoea

Image created by Dr. Philip Scott and provided by the National Animal Disease Information Service.

References

- Reist M. et al. (2011), Effect of Eprinomectin on milk yield and quality in dairy cows in South Tyrol, Italy. Vet Rec, 168:484.

- Verschave et al. (2014), Non-invasive indicators associate with the milk

yield response after anthelmintic treatment at calving in dairy cows. BMC Vet Res, 10:264. - McPherson W.B. et al. (1999), Proceedings of the American Association of Veterinary Parasitologists, 44th Annual Meeting, New Orleans, Louisiana, USA.

-

Image created by Dr. Philip Scott and provided by the National Animal Disease Information Service